No – the Euro is not a mistake

According to Hungary’s Central Bank Governor, Gyorgy Matolcsy, the introduction of the Euro was a mistake.

Foreword – my good old days at the University of Chicago

In 2006 I just started to attend the University of Chicago’s MBA program.

One of our first classes was Macroeconomics. It was taught by a professor whose style was, to say the least, direct. As were his teaching methods.

We had to crunch a few easy equations regarding two countries: one of them produced bread, the other country produced wine. We had to determine the price at which bread and wine would be sold (e.g. how many litres of wine equals 1 unit of bread).

This was one of the most boring things in my life ever. Or so it seemed. Wine and cheese?!?

We were pissed off that we had paid so much for such a seemingly basic education. It took me about 6 months until I got it. As the result was the clear separation of the “real” economy (a.k.a. goods markets) from money (a.k.a. financial markets) in my head. Not bad, at all.

And I even realized, based on this learning, that the two sides were linked: the price of things influenced real economy: the higher the price, the lower the demand.

Easy. Then we considered the same two countries with their own currencies and an exchange rate between these two currencies.

Again, the “real” economy is surely affected by the price of goods – and once there is export and import: the price of goods will depend on the exchange rate, as well:

COUNTRY A -> EXCHANGE RATE x PRICE OF THINGS -> COUNTRY B

Ahh and the Euro: later on we had to write a thesis for and against the Euro. Well – it was not easy, to say the least. As there were (and are) tons of pro’s and lots of con’s, as well. It is a very very complicated issue, to say the least.

The Euro problem – according to some (in November, 2019)

According to Matolcsy (the head of the Central Bank of Hungary), all elements for a successful joint currency are missing at the moment:

“a common state, a budget covering at least 15-20 per cent of the eurozone’s total gross domestic product, a eurozone finance minister and a ministry to go with the post”

He is right in these. Where Matolcsy is less than right follows.

The 20-years-of-Euro study – and its problems

To support his article Matolcsy quotes a study:

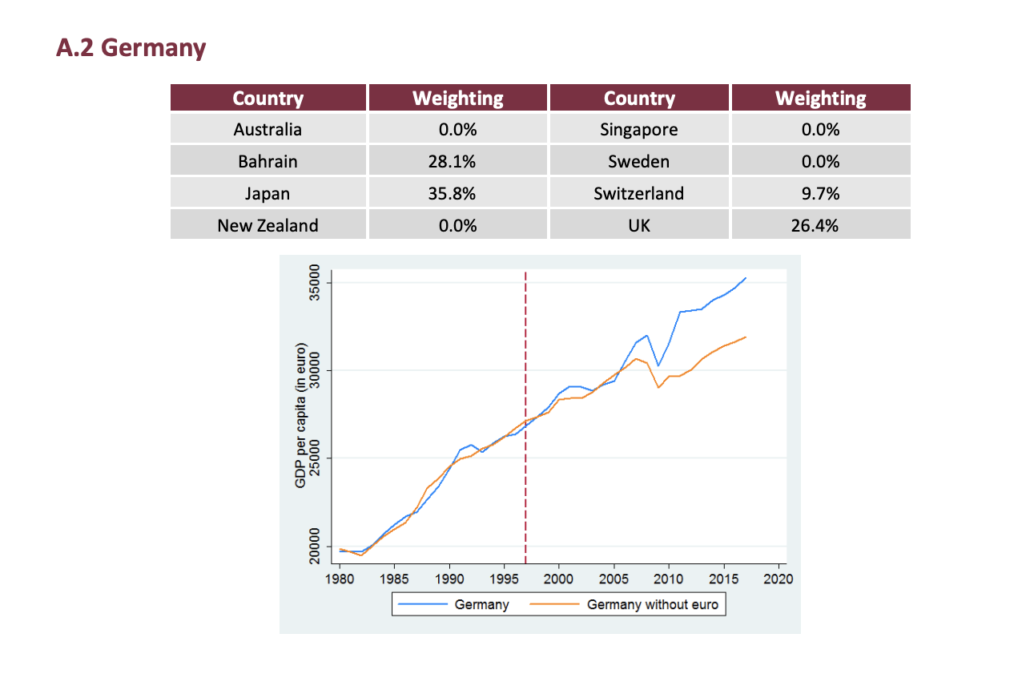

This study is “funny”, to say the least: according to this how much a given country won or lost with the Euro in 20 years can be calculated this way: you find a mix-of-countries for each country. This mix-of-countries is chosen based on how closely its mix-of-countries’ GDP per capita resembled that of the country in investigation before joining the Euro zone. e.g. for Germany: you see Bahrain 28.1%, Japan 35.8%, Switzerland 9.7% and UK 26.4%:

The method this Matolcsy-quoted study uses is as follows:

1-find a group of countries(!) whose GDP per capita values(!) before the introduction of the Euro, when combined (=take a weight and apply it to this group of countries data) resembles the most of the country we are investigating

2-then project the GDP per capita values for this group of countries into the future

3-compare these GDP per capita data points with the country we are investigating (e.g. Germany)

4-calculate the difference

So, again, the recipe suggested is: “take 28.1% Bahrain and take 35.8% Japan…” …and then claim that these countries’ past GDP per capita data, when combined, resembles the most of that of Germany. And that projecting these countries’ mixed economic growth into the future with some regression – and then to use it as a comparison is the way ahead is just questionable.

We just as well may be throwing darts.

Is there any better way to calculate the “what if”? For sure. If any of the readers up to it, I am happy to participate in a much better estimation than this.

Another problem: forgetting the end goal

There is one more problem: policy decisions are not made by economists but by politicians.

And for politics there is a short, medium and long term view.

Matolcsy is saying that it was a bad idea to introduce the Euro. I think it may have been – see more it below.

But for a thing like the EU (=unions of countries) things never work this way: it does not matter what happens in 20 years – what happens in centuries is what matters. So the real question is: will the Eurozone be better off, say, in 50 or a 100 years with the Euro?

Because the end goal is to create and sustain a real “economic power”: in simple language: the sum of the parts must be more than the parts alone. Any investigation should ask this question first – and not that what happened and happens to single countries.